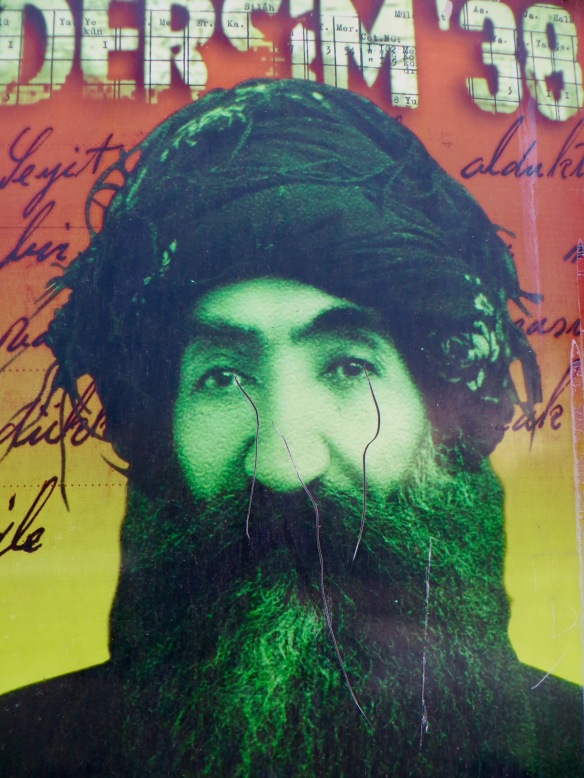

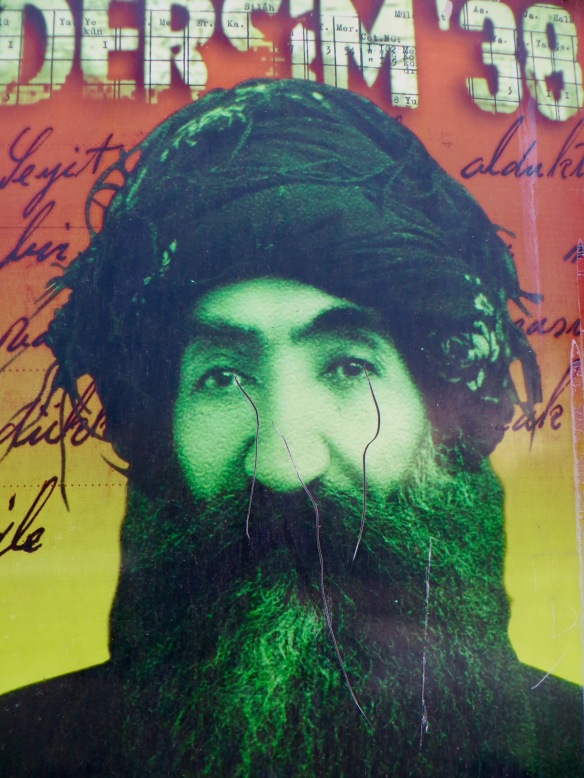

Back in Tunceli, I quickly freshened up at the hotel before going for a walk through the town centre, along the river and to the otogar to check whether minibuses left the following morning to Mazgirt (they did, but not at a time convenient for me). After ascending from the river through a park where many large snails crossed a stone footpath, thereby risking death under shoes worn by careless or vindictive humans, I came across two large plaques set into a stone wall reminding people about Dersim in 1938. On both plaques, males wore loosely tied turbans.

Perhaps the best of the easy-to-access accounts of the massacre in Dersim that began in 1937 and ended in 1938 is on the “Online Encyclopaedia of Mass Violence”, which has a case study entitled “Dersim Massacre, 1937-1938” last modified in 2012. Because so little is known about the massacre outside Turkey, I quote at length from it. As you will see, it has very obvious links with the Armenian genocide and its aftermath:

In 1937 and 1938, a military campaign took place in parts of the Turkish province of Tunceli, formerly Dersim, that had not been brought under the control of the state. It lasted from March 1937 to September 1938 and resulted in a particularly high death toll: many thousands of civilian victims. Contemporary officers called it a “disciplinary campaign”, politicians and the press, a “Kemalist civilising mission”. Prime Minister Tayyip Erdogan, however, in a November 2009 speech, referred to it as a “massacre”, which can be considered an historically appropriate term. It took place when the Republic of Turkey was consolidated – in contrast with the repression of the Kurdish Sheikh Said rebellion in 1925 or the Kocgiri uprising in 1921. The campaign in Dersim was prepared well in advance and therefore was not a short-term reaction to a specific uprising. President Mustafa Kemal Ataturk stood personally behind it and died shortly after its end.

Tunceli.

After the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne had recognised the Turkish nationalist movement as the sole legitimate representative of Turkey and admitted its victory in Asia Minor, the Republic of Turkey was founded. The nationalist movement implemented revolutionary changes from above, such as the abolition of the caliphate in 1924, the introduction of the Swiss civil code in 1926 and the Latin alphabet in 1928. Broadly acclaimed as a successful modern nation state, the Turkish Republic rebuilt its international relations in the 1930s and succeeded, in a deal with France and the League of Nations (of which it became a member in 1932), in incorporating the Syrian region of Alexandretta into its national territory in 1938 and 1939. However, radical Turkism (Turkish ethno-nationalism) with racist undertones marked the ideological climate of the 1930s, while cosmopolitan Ottomanism and Islam were radically evacuated from the political sphere and intellectual life. Kemalist Turkism, the ideology of the new political elite tied to the one-party regime, albeit triumphalist, expressed the need for a connection to deeper roots and made a huge effort to legitimise Anatolia as the national home of the Turks by means of historical physical anthropology.

The region of Dersim, renamed Tunceli in 1935, stood markedly at odds with the politico-cultural landscape of 1930s’ Turkey. In a 1926 report, Hamdi Bey, a senior official, called the area an abscess that needed an urgent surgeon from the republic. In 1932, the journalist and deputy Nasit Ulug published a booklet with the title “The Feudal Lords and Dersim”; it asked at the end how a “Dersim system” marked by feudalism and banditry could be destroyed. Hamdi Bey, General Inspector Ibrahim Tali, Marshal Fevzi Cakmak and Minister of the Interior Sukru Kaya collected information on the ground and wrote reports concluding the necessity of introducing “reforms” in the region. The need for reforms for Dersim, together with military campaigns to effect them, had been a postulate since the Ottoman reforms, the Tanzimat, of the 19th century. Several military campaigns had taken place, but had brought only limited successes. In parts of Dersim and other eastern regions of the Ottoman Empire, in which Kurdish lords had reigned autonomously since the 16th century, the state had established its direct rule only in the second third of the 19th century, though it depended still in the republican era on the co-option of local lords to maintain its rule. The central parts of Dersim, by contrast, resisted both co-option and direct rule until the 1930s. Nevertheless, Dersim had been represented by a few deputies in the Ottoman parliament in Istanbul and, since 1920, in the national assembly in Ankara.

Tunceli.

Dersim is a mountainous region between Sivas, Erzincan and Elazig (renamed from Elaziz in 1937. Turkification of local names began during world war one). It covers an area of 90 kilometres from east to west and 70 kilometres from north to south, and had, according to official estimates in the 1930s, a population of nearly 80,000, of which one-fifth were considered men able to bear arms. Dersim’s topography allowed cattle breeding, but only little agriculture. It offered many places for refuge and hiding: valleys, caves, forests and mountains. These had been vital for the survival of Dersim’s Alevi population. The Alevis venerated Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law. They refused to conform with sharia and remained attached to unorthodox Sufi beliefs and practices widespread in Anatolia before the 16th century, when the Ottoman state embraced Sunni orthodoxy. Their beliefs were mostly linked to Anatolian saint Haci Bektash (13th century). Since many Alevis had sympathises with Safavid (and Shia) Persia in the 16th century, they were lastingly stigmatised as heretics and traitors.

The first language of the Dersim Kurds, as they were called by contemporary observers, was not Turkish but Zazaki (the main language) or Kurmanji. Kurdish nationalism had had an impact on a few Dersim leaders and intellectuals since the early 20th century. They supported President Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self-determination after world war one and linked an articulated ideology to Kurdish activism, as General Fevzi Cakmak complained in his 1930 report. Cakmak therefore demanded the removal of functionaries of “Kurdish race” in Erzincan. The Kocgiri uprising in 1921 had been the first rebellion marked by overt Kurdish nationalism; it, too, had taken place in an Alevi region at the western boundary of Dersim.

Though the declaration of a secular republic and the abolition of the caliphate in early 1924 won over many Anatolian Alevis, most Alevis in eastern Anatolia remained distrustful. This divide coincided by and large with that of Turkish- and/or Kurdish-speaking “eastern Alevis” outside the organisation of the Bektashis on the one hand, and “western Alevis” reached by the reformed Bektashi order of the 16th century and thus domesticated by the Ottoman state on the other. Dersim had important places of religious pilgrimage, some of which were shared with local Armenians. Its seyyids claimed descent from Ali and entertained a network of dependent communities in and outside Dersim. The Young Turks and the leaders of the Turkish national movement after 1918 had co-opted the Bektashis, of which a leader had in vain tried to win over the chiefs of Dersim to fight alongside the Ottoman army against the invading Russians in 1916. Two limited rebellions then broke out and armed groups harassed the Ottoman army. Dersim was the only place more or less safe for Armenian refugees during and after the genocide of 1915, which mainly took place in the eastern provinces.

Tunceli.

After the establishment of the new state in Ankara and the repression of the Kurdish uprisings of the 1920s, the attention of the government turned more and more to Dersim, described as a place of reactionary evil forces, of interior and exterior intrigues, and hostage to tribal chiefs and religious leaders. Dersim could, in fact, be described as a pre-modern, tribally split society; it became increasingly isolated after 1920. At the same time, according to Hamdi Bey who visited Dersim in 1926, it was growing more politicised – to the point of adopting openly anti-Kemalist Kurdish positions. Sustained contacts with Hoybun, the Kurdish and Armenian organisation founded in Syria in 1927, were not, however, possible.

Economic problems and banditry had a long history in Dersim; they became more acute due to the region’s isolation and the bad economic conditions after world war one. Yet, in the late Ottoman era, new currents had begun to permeate Dersim and the areas adjacent to it. These included labour migration, emulation of quickly modernising Armenian neighbours, the desire for education and attendance at new – Armenian, missionary, or state – schools, as well as the spread of medical services. Compared with the situation in the early republic, late Ottoman eastern Anatolia had been pluralist and culturally and economically much more dynamic.

The 1934 Law of Settlement legitimised in general terms the depopulation of regions in Turkey for cultural, political or military reasons, with the intent to create, as Minister of the Interior Kaya stated, “a country with one language, one mentality and unity of feelings”. The law was conceived in order to complete the Turkification of Anatolia in the context of the new focus on Dersim in interior politics.

Tunceli.

In October 1935, Italy began a brutal invasion of Ethiopia during which it used chemical weapons and killed hundreds of thousands of men, women and children. For the prominent theorist of Kemalism at the time, deputy and former minister Mahmut Esat Bozkurt, Mussolini’s fascism was nothing other than a version of Kemalism, even though Turkey’s and Italy’s foreign policies contrasted. In 1930, Bozkurt had spoken of a war between two races, the Kurds and the Turks, and had gone so far as to say, “All, friends, enemies and the mountains, shall know that the Turk is the master of this country. All those who are not pure Turks have only one right in the Turkish homeland: the right to be servants, the right to be slaves.”

These elements formed the context when, in December 1935, Minister of the Interior Kaya presented a draft law, commonly known as the Tunceli Law, that once more labelled the region a zone of illness that needed surgery. In terms of national security there was no urgency; non-military officials of the state were not molested on entering Dersim, e.g., for the population census of every village in 1935. The law passed without opposition in the national assembly or the press, both being controlled by the Kemalist People’s Republican Party. Dersim, formerly part of the province of Elazig, was established as a separate province, renamed Tunceli and ruled in a state of emergency by the military governor, Abdullah Alpdogan, the head of the Fourth General Inspectorate…

Hamdi Bey’s 1926 report had already called for strong measures and labelled the attempt at a peaceful penetration of Dersim by schools, infrastructure and industry an illusion. Against this background, actors on both sides were separated by a rift and unable to find a common language, albeit in an unbalanced dialogue. Seyyid Riza, perhaps the most important tribal chief, in addition to being a religious figure, insisted on autonomy and the revocation of the 1935 Tunceli Law. He seemed to have believed initially that Dersim could not be subdued militarily. He had worked for years, partly successfully, to unite the tribes.

Tunceli.

After several incidents in March 1937 which included attacks by tribal groups against the new infrastructure in Pah and a police station in Sin, the military campaign was launched. With 8,623 men, artillery and an air force at its disposal, Ankara possessed superiority in numbers and materiel. On 4th May 1937, the Council of Ministers, including Ataturk and Fevzi Cakmak, the Chief of General Staff, decided secretly on a forceful attack against western central Dersim, an attack to kill all who used or had used arms and to remove the population settled between Nazimiye and Sin. The same day, planes dropped pamphlets saying that, in the case of surrender, “no harm at all would be done to you, dear compatriots. If not, entirely against our will, the [military] forces will act and destroy you. One must obey the state.”

In the following months, the army successfully advanced against fierce resistance and changing tribal coalitions led by Riza, allied tribal chiefs and Aliser, a talented poet and activist. Unity among the rebels was far from achieved; only a few tribes formed the hard core of the resistance. On 9th July, Aliser and his wife were killed by their own people and their heads sent to Alpdogan. Also in July, Riza sent a letter to the Prime Minister in which he vividly described what he saw as anti-Kurdish policies of assimilation, removal and a war of destruction. Via his friend Nuri Dersimi, who had gone into exile in Syria in September 1937, he also sent a despairing letter to the League of Nations and the foreign ministries of the United Kingdom, France and the United States, none of which answered. On 10th September, he surrendered to the army in Erzincan. Messages of congratulation were sent to Alpdogan by Ataturk, Minister of the Interior Sukru Kaya and Prime Minister Inonu, who had visited Elazig in June. Shortly before Ataturk visited Elazig, Riza was executed in the city together with his son, Resik Huseyin, tribal leader Seyit Haso and a few sons of tribal chiefs. The executions were hastily organised by Ihsan Sabri Çaglayangil, later the Foreign Minister.

Despite the setbacks of 1937, Dersimi groups resumed attacks against the security forces in early 1938, saying that they would all perish if they did not resist. The military campaign took on a new and comprehensive character as the government embarked on a general cleansing in order “to eradicate once and for all this (Dersim) problem”, in the words of Prime Minister Celal Bayar in the national assembly on 29th June 1938. Also in June 1938, military units began to penetrate those parts of Dersim that did not surrender between Pulur (Ovacik), Danzik and Pah. On 10th August, a large campaign of “cleansing and scouring” started. It ended in early September and cost the lives of many thousands of men, women and children, even of tribes that co-operated with the government.

Tunceli.

According to official statements, the military campaign of 1937 targeted bandits and reactionary tribal and religious leaders who misled innocent people. On a secret level, however, right from the beginning – in particular, with the decision of the Council of Ministers of 4th May 1937 – groups of the people of Dersim as a whole were targeted, at least for relocation as allowed for by the 1934 Law of Settlement. Those targeted feared, as in Kocgiri in 1921, that they would perish like the Armenians if they did not resist. The campaign in spring 1937 concerned the regions in which most clashes occurred, between Pah and Hozat. Villages were to be disarmed and people removed, but the main violence targeted armed groups.

Halli, who amply cites military documents, scarcely uses the word “imha” (annihilation, destruction or obliteration) for this period. This changed with the summer 1938 campaign, which employed massive violence against the whole population, even beyond the parts of Dersim that did not surrender and that had been declared prohibited zones under the Law of Settlement. The Council of Ministers decided on 6th August 1938 that 5,000 to 7,000 Dersimis had to be removed from the prohibited zones to the west. “Thousands of persons, whose names the Fourth General Inspectorate (under Alpdogan) had listed, were arrested and sent in convoys to the regions where they were ordered to go,” wrote Halli in 1972.

Also targeted for relocation were numerous families living outside these zones or in areas neighbouring Dersim, if they were considered members of Dersimi tribes. Notables living outside Dersim were killed in summer 1938, as were some young Dersimis doing service in the army. For the killing of surviving “bandits”, an order by the Prime Minister, the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Defence and the Military Inspectorate proposed to use the Special Organisation, known for its role in the mass killing of Armenians in 1915 and 1916, and the murder of targeted individuals.

Tunceli.

According to Halli, “thousands of bandits” were killed in the first week of “cleansing and scouring” from 10th to 17th August 1938, but he mentions no comprehensive number for all those killed during the whole campaign. From his detailed narrative, however, which gives precise numbers or mentions a “big number” of killed persons for dozens of incidents, deaths likely totalled considerably higher than 10,000. An unpublished report by Alpdogan’s Inspectorate, recently quoted in Turkish newspapers, mentions 13,160 civilian dead and 11,818 deportees. The high number of deaths and ample written evidence prove that the killings were not limited to the insurgent tribes alone. A comparison of the censuses for 1935 and 1940 shows that the district of Hozat, with a loss of more than 10,000 people, was the most seriously affected part of Dersim. A proposed number of 40,000 victims seems, however, implausibly high.

According to Caglayangil, the army used poison gas to kill people who hid in caves. Many others were burned alive, whether in houses or by spraying individuals with fuel. Even if people surrendered they were killed. In order “not to fall into the hands of the Turks”, girls and women jumped into abysses, as many Armenians had in 1915. The suspicion of having lodged “bandits” or, according to witness accounts by soldiers, military units’ desire for vengeance, sufficed as justification to kill whole villages. Soldiers confirm that they were ordered to kill women and children. One has to bear in mind that the Dersimis were seen – and declared so by officers – as Alevi heretics, sometimes as crypto-Armenians. When jandarma posts were established in the 1930s, jandarma even investigated whether local young men were circumcised. Uncircumcised men were thought to be Armenians.

“It is understood from various sources that, in clearing the area occupied by the Kurds, the military authorities have used methods similar to those used against the Armenians during the Great War: thousands of Kurds including women and children were slain; others, mostly children, were thrown into the Euphrates; while thousands of others in less hostile areas, who had first been deprived of their cattle and other belongings, were deported to vilayets in Central Anatolia,” reported the British Vice-Consul in Trabzon on 27th September 1938. His report is the exception to the rule that there exist no reports by foreign observers in or near the theatre of events because Dersim and the whole of eastern Turkey were generally closed to foreigners.

Documents and testimonies relating to the massacres do exist… They all agree that systematic massacres took place. Soldiers and survivors add that targets included civilians, women and children.

Accustomed to looking up to the state and army as omnipotent entities, most soldiers feared even decades afterwards to speak about their experiences. However, in 1991, Halil Colat, an ex-soldier, said, “When we came to the headquarters, we learned that discussions had taken place between the officers. A few said that these people (women and children in Hozat who had not given information on the whereabouts of the men) had to be annihilated, but others said that this was a sin… They (finally) ordered us: ‘Annihilate all you can apprehend…’ And that day, we soldiers, in a horrific savageness and craziness, gathered the women, girls and children in a mosque – it was in fact not like a mosque, but rather like a church – closed it, sprayed kerosene and easily burnt them alive.”

Tunceli.

Dersimis themselves have collected an important number of private documents, conducted interviews and built up internet sites. Recent work has added important material. A scholarly “1937 to 1938 Dersim Oral History Project” was launched in 2010. However, a main archive or centre of documentation for the Dersim massacre does not yet exist. The only nearly contemporary Kurdish history of the event is a chapter in Nuri Dersimi’s book of 1952, which includes testimonies. The author himself had left Dersim before the campaign.

Documentary novels and memoirs of the period have been written since the 1980s, e.g., by Sukru Lacin, a founder of the Turkish Workers’ Party in 1963 and not a sympathiser with Riza or Kurdish nationalism… Lacin confirms that the campaign of 1938, and the forced removal of populations, covered parts of Dersim such as Mazgirt, Pertek and Nazimiye that did not refuse to pay taxes or enlist people in the army. He confirms that villages in Erzincan province in the districts of Refahiye, Cayirli, Uzumlu, Kemah and Tercan, where relatives of Lacin lived, were also targeted because their inhabitants were Alevi Kurds and were said to have relations with Dersim.

In the years after 1938, the one-party state and its press continued to maintain the image and memory of a necessary and fully successful campaign of pacification followed by sustained efforts at reconstruction. This is also the content of the book entitled “Tunceli is made accessible to civilisation” published in 1939 by Nasit Ulug, then the director of “Ulus”, a daily newspaper. Ulug described the punishment of “bandits”, but made no reference to mass killings. He provided a panegyric to the Turkish army, to which the Turkish nation had once again to be infinitely thankful… The Western and the Soviet press largely followed the Kemalist narrative of a civilising mission against reactionary conservatives. Only the press in the USA seemed to voice criticism of both the violent campaign and its undemocratic political framework. Like the European press, however, it lacked independent sources of information.

Heroic reports that recounted Kurdish exploits, resistance and the foundation of an independent Kurdish government appeared in the Armenian press in 1937. A simultaneously tragic and heroic memory of Dersim in 1937 to 1938 is to be found in the 1952 book and the memoirs of the Kurdish nationalist Nuri Dersimi, who was in contact with Armenians since the beginning of his exile. Dersimi’s texts, which underlined the barbaric aspects of the campaign, were seminal for the memory of the Kurdish nationalists, but he was also criticised by Dersimis as an instigator who left the country when it became dangerous.

The one-party regime met its end in the years after 1945. In 1947, the government repealed the Tunceli Law and relocated people were allowed to return to their villages. The state of emergency was lifted in 1948. Henceforth, memories dissenting from those promoted by the former one-party regime as well as on-going realities in Tunceli – poverty, the absence of schools and health services, etc. – could be acknowledged, though not freely. The army, the main actor on the ground, as well as the state and its founder, Ataturk, who had stood behind the Tunceli campaign, could never be openly criticised. The memory of the Dersim campaign as at least partly ruthless and misguided can also be found in letters of pious soldiers to the spiritual father of the Nurculuk, Said-i Nursi.

After 1945, Turkey stood under the shadow of the Cold War. Right and left claimed Ataturk’s heritage and did not question dark sides of the Kemalist “civilising mission”… The memory of the Dersim campaign as mass violence by the state and its army was nevertheless articulated in leftist circles, in particular among leftists from Tunceli, but also more generally among those with Alevi and Kurdish backgrounds.

The military putsch of 1980 crushed the Turkish left. After this experience, leftist circles critical of the state began to be more open to the Kurdish perspective that the Turkish state had always reacted with mass violence and denial against even moderate Kurdish claims. More detailed memories, detached from the Kemalist state and ideologies of progress and civilisation, have been recounted since the late 20th century. A “renaissance” of long-suppressed ethnic and religious identities and histories took place at the dawn of the post-Cold War era. Turkey’s EU candidature in 1999 and the AKP government since 2002 contributed to a more liberal context in which the military, the main actor of the campaign of 1937 to 1938, partly lost for the first time its hitherto sacrosanct and unchecked position at the top of the state.

During the so-called Kurdish or democratic opening of autumn 2009, on 17th November, Prime Minister Erdogan called the events of 1937 to 1938 a massacre. For the first time, the memory of the Tunceli campaign as one of pacification and a mission of civilisation was publicly challenged at the governmental level, whereas the Republican People’s Party, that ruled Turkey when only one political party existed, had trouble in defending what for 70 years had been the official version of history. The latter version is nowadays widely seen as unacceptable, as is evident in media discussions from autumn 2009 onwards. It appears today as the position only of Turkish ultra-nationalists.

In contrast with the aftermath of the Kocgiri revolt in 1921, there were neither critical discussions in the Turkish national assembly nor legal claims that officers responsible for brutality and mass killing of civilians should be put on trial. This is even less the case for Dersim because the Law of Settlement and the Tunceli Law had prepared the legal framework for the campaign and the removal of the Dersimis in advance… Legalism disguised the breach of law against citizens, as in other authoritarian or fascist regimes of the 1930s…

Historical sociologist Ismail Besikci was the first scholar to research the Dersim campaign; to emphasise the legalist but illegitimate, anti-constitutional framework in which it took place; and to call it, in a book of 1990, a genocide. Anthropologist Martin van Bruinessen proposed, in an article of 1994, the label “ethnocide”, arguing that the destruction of Dersim’s autonomous ethnic culture, not of its population, had been the campaign’s main intention. Though declared as a Turkifying mission of civilisation, the intent “to destroy, in whole or in part” – according to article 2 of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide – the Dersimis, as a distinct ethno-religious group, then labelled as Alevi Kurd and partly as crypto-Armenian, and of “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” is manifest. This is well documented. In a comparative legal perspective, Besikci’s position may be supported by later jurisdiction based on the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide as by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia.

A restrictive historiographical use may, however, reserve the term genocide for mass killings of the 20th century in which a higher proportion of a larger ethno-religious group was killed and the future of the whole group in its habitat was destroyed, as in the case of the Ottoman Armenians or the European Jews. In both latter cases, those responsible considered the targeted groups to be inassimilable to the nation. The Dersim massacre concerned parts of the Dersim population, whereas other parts were removed and the main part could remain in place. As a result, the area’s informal autonomy and, in part, its ethno-religious habitat were suppressed. Extermination in 1938 had targeted first those whose tribes and families were involved in the resistance. But it also included others, among them relatives who were not in the resistance, and even people living outside Dersim. Principally, however, the Kemalists who were responsible for the campaign considered that the Dersimis could be assimilated into the nation state.

In studies on Turkey across all disciplines, the Dersim campaign remained under-researched until the late 20th century. One scarcely finds mention of it in the major university textbooks on Turkish history. To this day there still do not exist monographs or detailed research articles in Western languages, except the translation of Besikci’s book and a few articles or book chapters. The dark sides of Turkey’s foundation and early history, from the Young Turks’ one-party regime to the Dersim campaign and later pogroms against non-Muslims, have long been under-researched both inside and outside Turkey for political reasons and because of simplistic notions of progress versus religious reaction in Western scholarship on Turkey.

In recent years, a fresh look at these topics and the Dersim campaign has finally emerged. The fresh look includes the particularly silenced Armenian aspects of Dersim – a dimension that Western scholarship long failed to grasp. The lack of access to the military archives, however, said to be in the process of classification, seriously hampers comprehensive research on the Dersim campaign. The military archives could answer questions such as the hierarchical level at which the order was given to massacre people, women and children included; to what extent poison gas was used against people in caves; and whether there were, as it seems, absolutely no orders against or punishments for widespread brutalities such as burning alive, slashing open pregnant women and stabbing babies.

In contrast to state-centred rightist or leftist traditions – which explained the high number of civilian dead to be collateral damage of a necessary campaign against reactionary rebels – recent scholarship elaborates on the problematic aspects and the victims of the Dersim campaign. It puts it in the context of the Republican People’s Party’s suppression of any opposition. It frames it as an ethnocide, the “deliberate destruction of Kurdish ethnic identity by forced assimilation”. It also sees it as a genocide committed against the backdrop of a colonialist enterprise, bearing in mind that the Turkish political elite did not know “Kurdistan” any better than 19th century European elites had known their overseas colonies. Another interpretation stresses the logical and chronological coincidence with the Turkish History thesis that claimed Anatolia to have been for thousands of years the home of the Turks (utter nonsense, of course) – a racial speculation that revealed an aporia of legitimacy and a dead-end of ultra-Turkist Kemalism. It implied the wish to make disappear all remaining vestiges of non-Turkish presence and heterogeneous Ottoman co-existence. These vestiges reminded state-centred elites of a period for which they felt distress and shame; a period marked by the tedious Oriental Question, in particular the Armenian Question, and by the lack of governmental sovereignty. It involved a deep-seated fear of de-legitimisation.

Tunceli.

Once home and in possession of the information above, a lot of what I saw and heard in Dersim made more sense. I understood far better why so many Kurds, whether Alevis or not, called Ataturk a dictator and/or a fascist; why Alevis in particular had such distrust for Sunni Muslims, Turkish nationalists and uniformed representatives of the state; and why almost all Dersimis lacked confidence in the government in Ankara, which only in the last decade or so had sought to provide the people of Dersim with the services, facilities and opportunities accessible to Turkish citizens almost everywhere else in the vast republic. But I also understood far better why the expressions of friendship between Armenians and non-Armenians had a sincerity in Dersim greater and more convincing than in any other region of Turkey I had visited in recent years. Note that Armenians and Alevis shared some sites of religious pilgrimage; that “Dersim was the only place more or less safe for Armenian refugees during and after the genocide of 1915”; that “crypto-Armenians” lived in Dersim in the 1930s (and some still did, but in reduced numbers); that Armenians and Kurds worked together to further matters of mutual concern and/or interest; that Dersimis felt they had to resist state oppression in the 1930s if they did not want to perish in the same way as the Armenians in 1915 and thereafter; and that, in order “not to fall into the hands of the Turks”, Kurdish girls and women “jumped into abysses, as many Armenians had in 1915”.

But the above also begs the following question. Did the Dersimis suffer an act of genocide in 1937 and 1938 just as the Armenians had in 1915 and thereafter? Despite far fewer Dersimis being massacred in 1937 and 1938 than Armenians in 1915 and thereafter, the evidence above is extremely persuasive. Because events in Srebrinica in 1995 have been declared an act of genocide, the ones in Dersim and elsewhere in 1937 and 1938 must also be genocide. What is interesting is that a growing number of Turkish nationals who are not Kurdish or Alevi believe that genocide took place, and many more will believe the same when scholars can access official documents in greater quantity.

By the way. Note the intriguing reference above to “a mosque – it was in fact not like a mosque but rather like a church” in the quote attributed to a soldier involved in a particularly brutal, upsetting and wholly unjustifiable event during the massacre. I think we can safely assume that the soldier refers to a cemevi. If referring to a cemevi, his ignorance about Alevis is revealing. Perhaps he was a conventionally pious Sunni Muslim who had never shown the least interest in Alevis because they were regarded as heretical in the extreme, or perhaps he was so imbued with the radical atheism of the Turkish Republic of the 1930s that he distrusted everyone with religious convictions. Alternatively, he may have bought completely into the Turkish nationalism of the time, which, while admitting that Kurds existed, regarded them as an inferior race of people who needed “civilising” by assimilation or, if averse to assimilation, extermination. However the soldier regarded the Dersimis at the time of the massacre, he lacked empathic understanding for people who differed from him. Hmmm. Does a similar lack of empathic understanding prevail among members of some or all of today’s brutal Islamist groups, the vast majority or which are Sunni Muslim? I think it does. Such groups currently operate around the world with a blood-lust that cannot fail to shock the vast majority or people, whether they have a religious commitment or not.

Tunceli.

Although it was Sunday, some of the shops in the pazar were open, so I bought a few things to eat on my balcony (I did not feel like a full meal, despite not eating much during the day, but resolved that I would have a treat in a lokanta the following evening to bring to an end my brief stay in Tunceli, a town that by now I was slightly in love with, not least for the wonderfully forthright and friendly women who thought it was wonderful that a foreign male was daft enough to stay in their infrequently visited home town). I bought a small pot of honey still in its comb that had come from Ovacik, a large pot of yoghurt which I could chill in the fridge in my room if it remained unfinished and a bottle of Efes Malt, the latter for the very reasonable price of 4.5TL. I sat on the balcony and, as I ate and wrote, remembered all the things I had done in the day. The wind picked up not long before nightfall. Dark clouds hung over the mountains to the south-west and thunder and lightning added a sense of drama before rain fell with heavy droplets. Open businesses closed for the day and the streets began to empty. By 9.00pm I could hear only the rain, a few muffled voices and the occasional car engine firing up.

Before going to sleep, I thought about two women without headscarves in their late twenties or early thirties who sat in a posh pastane near the otogar and flirtatiously waved and smiled when I walked past them, of a woman with a headscarf who played backgammon with a male friend in one of the tea houses in the pazar, and of the encounter I had had with the two female high school students on the minibus that dropped me at Asagitorunoba. I also thought of the women in Asagitorunoba who chatted and smoked cigarettes with exactly the same relaxed informality as their male companions.

Tunceli.

What was it that so many Sunni Muslims found threatening about such encounters between males and females? Moreover, segregation of the sexes did not mean that girls and women were less prone to violent assault, sexual or otherwise, than in nation states where it was absent. Evidence from many nation states where there was de jure or de facto segregation of the sexes suggested that women suffered more violence at the hands of males, not less. There was also evidence that the sexual abuse of boys and young males was higher in nation states where the sexes were segregated. A dreadful case of large-scale child sexual abuse in Pervari a few years ago led to revelations that such abuse was widespread in Turkey. Indeed, statistics suggested that child sexual abuse in Turkey was far greater than in the UK.