Because the road to Sagman began beside the reservoir and Sagman was high in the hills and mountains, the ascent was quite demanding for someone aged over 60, and it was made a little more challenging because the village was 10 kilometres away. Moreover, at only one point could I get fresh water, at an improvised cesme dependent on a hose to bring liquid refreshment to people on the road. But the views over the reservoir and the surrounding hills and mountains were never less than excellent and two men kindly gave me a lift for the last 3 kilometres. Sagman was a predominantly modern village that clustered quite tightly around a recently built mosque, but, because it lay on a gently inclined slope dominated by pasture with stunning views in all directions, I found it most attractive, the pitched roofs covered with corrugated iron included. By now there was some bright sunshine and I felt elated.

View south from the road to Sagman.

View south from the road to Sagman.

I was dropped in what passed as the centre of the village, a small open space enclosed by a few buildings, two shops included. There were also some parked motor vehicles, three of which were minibuses that carried people to school, Tunceli or Elazig. After admiring the extensive views over the pasture toward hills, mountains and the reservoir, I set off along a dirt road that led after about 2 kilometres to the mosque and the castle that were Sagman’s main claims to fame (the old town of Sagman, which had now almost completely disappeared, was located close to the castle and around the mosque. The present village cannot be more than 50 or 60 years old). The road for most of the way was level or gently inclined in my favour, which made the walk an easy one. Mules and horses in a quantity not witnessed previously during the trip ate the pasture and looked in good health. At the easternmost extremity of the village, a jandarma post was still occupied by men in uniforms.

View south-east from Sagman.

I turned a corner and ahead was the mosque in front of the castle. Both had been built at more or less the same height above sea level, but a distance of about 250 metres lay between them. The castle was on an eruption of rock a little higher than all the ones near it and the mosque was above a slope descending to a river far below to the south. Both structures were surrounded by stunning upland scenery of mountains and deep valleys. I was thrilled by the prospect of looking around for about an hour or so.

The mosque and castle, Sagman.

The mosque was benefitting from a substantial restoration programme, but the day of my visit, no workmen were present. This meant I could walk where I wanted. Sinclair notes that:

The domed prayer hall, executed in black basalt, and the portico in front were built probably about 1555… The wings either side, including the turbe reached from the s. side of the w. wing, must have been added about 1570. To all appearances these wings are a tekke, a lodge for dervishes of a particular (Sufi) order. The use of the mosque as part of a tekke would not have prevented members of the town’s population from worshipping in the prayer hall…

Prayer hall. The n. wall is distanced from the dome so as to contrive an arched entrance space almost covering the length of the prayer hall’s n. side… The comparatively simple mihrab has a frame of muqarnas as well as a muqarnas vault. The small stone member has five niches with pointed arches at the base on each side. These are pabucluks (cubby-holes for shoes). In the tower-like part beneath the pulpit are further cubby-holes…

The prayer hall is entered through a portal in whose muqarnas vault genuine stalactites are formed. Apart from this and the decoration of the engaged pillars on the corners between the bay and the outside face, the portal is plain: however, it is executed in a remarkable conglomerate stone white and pink in colour…

The mosque, Sagman.

E. and w. wings. To e. and w. of the portico, there is a row of rooms consisting of a vaulted rectangular chamber, a second, narrow, vaulted room and a third, domed one at the end…

To the w. the octagonal turbe is bonded with the complex of rooms: its north face is formed by part of the back wall. Its low sides are executed in an alternation of black and white courses.

The mosque, Sagman.

The mosque, Sagman.

The mosque, Sagman.

When the restoration project is complete, the mosque will probably look very much as it did when originally constructed. Without question, this proved to be the day’s most remarkable survival from the past, although the nearby castle also had its rewards. As Sinclair reveals:

What survives is the walls fortifying the westerly arm of the castle rock, i.e. that pointing towards the mosque… The corner of the n. and sw. faces is of cut stone, and so is the polygonal, but slight, tower in the middle of the sw. face. Otherwise the masonry is of uncut or roughly hacked blocks. It is reminiscent of that of the castle of Pertek. The two walls are built above vertical cliffs. The extent and configuration of the rest of the castle has not been investigated. ? 16th century, but certainly the reconstruction of a previous castle.

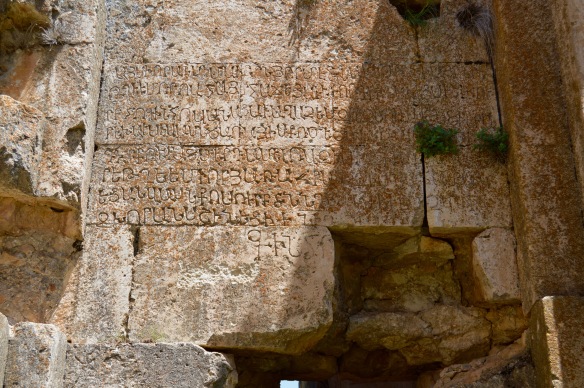

The castle, Sagman.

Just north of the mosque was a cesme with two vaulted bays. The cesme was built in 1555 by a local Kurdish ruler called Bey Keykusrav, who may have also built the mosque. Bey Keykusrav was the father of Salih, the prince who was buried in the turbe.

The cesme, Sagman.

It was on land between the castle and the mosque, but a little to the north of the former, that a cluster of houses marked where at least part of the old town of Sagman stood until the 1980s. Today, however, only traces of the foundations of the houses remained among trees and undergrowth of recent pedigree.

Half way through my look around, I met two elderly couples who had driven to this quiet but beautiful spot to eat a picnic and walk along paths disappearing as the grass and flowers took over. Both couples appeared to be Sunni Muslims, but I could not fault their friendliness. I was asked to eat some food, but declined the invitation because it was now about 4.00pm and I was not sure how long it would take to get back to Pertek.

Sagman.

I continued to chat with the two men as I drank water from the cesme. I had seen on arrival an old dirt road leading from beside the mosque into the valley to the south and asked the men where it went. They said that it was the old road from Pertek which, for the last 5 or 6 kilometres, was no longer used by motor vehicles destined for Sagman because it had not been maintained for many years. Nonetheless, it could be walked along and, from where the road was still accessible to motor vehicles, from a very small but largely deserted village one of the men identified as a mahalle, I might find a car going to Pertek. When it was suggested that Pertek lay about 12 to 14 kilometres from the mosque, I thought the walk would be worth the gamble. To return the way I had come might involve a walk just as long, but still leave me about 8 to 10 kilometres from the hotel. I was told to take a left just before the mahalle, or the first village after leaving the mosque, and warned that I would have to first descend to the river before ascending the other valley wall and taking a right to Pertek. By now, a little rested and with a bottle full of water from the cesme, I was keen to press on. If nothing else, I would see more of the uplands of Dersim that had so captivated my imagination. I shook hands with the two men who said I should arrive in about two hours at an inhabited village about 3 kilometres from Pertek.

The castle, Sagman.

By now, the cloud had built up again and I set off at a brisk pace knowing the cooler conditions would militate against getting overheated. I kept turning back because the views of the castle were particularly good, but there were also moments when the mosque was silhouetted against the grey sky. The valley into which I rapidly descended could not be faulted either and, the lower I got, the more I encountered trees and undergrowth. When I looked up, mountains enclosed me. I felt elated all over again.

Between Sagman and Pertek.

The mosque and castle, Sagman.

I arrived at a left turn but, to confirm it was the correct one, walked a little further to ensure the village was nearby. It was nearby and, at the point where the road came to an end, someone had parked a very old car. This implied that at least one house in the village might still be lived in, but when I looked around, most of the narrow paths leading from one house to another were overgrown or breaking up. The houses had been built on the steep south-facing slope in such a way that no house obscured the view of another. The houses utilised a light brown stone and had flat roofs, but none appeared to be inhabited. Some roofs had been covered with large blue tarpaulin sheets weighed down with stones. The tarpaulin sheets were intended to keep the rain from penetrating inside, which made me think the owners of the houses had plans to restore them, perhaps so they could use them during the summer months. I looked around and could not think of many more pretty places to have a house. Moreover, it was from the village that the road could be driven along, albeit with care.

The almost deserted village between Sagman and Pertek.

The almost deserted village between Sagman and Pertek.

The almost deserted village between Sagman and Pertek.

By now the wind was building up and, about half a kilometre from the village, rain began to fall from a sky full of grey cloud, thunder and lightning. I had my anorak with me, so I put it on and zipped it up. The rain persisted for about half an hour, but I pushed on because there was no shelter beside the road. During that half hour, I passed two very large flocks of sheep being brought down from the pasture on the mountain slopes and chatted with two young shepherds smoking cigarettes under an umbrella. The young shepherds alarmed me when they said that Pertek was still 10 kilometres away (luckily, they were wrong). I then arrived at the point where a bridge crossed the river. A steep ascent out of the valley lay ahead, which I knew would test my increasingly tired legs, but I was now about half the way to my destination. As the rain eased and then stopped altogether, I saw that semi-nomadic families had set up a camp not far from the bridge on a patch of level ground wider than anywhere else nearby. The shepherds I had spoken with earlier would no doubt spend the night in one of the tents. Their sheep would be put into pens made with wooden fencing. An open-topped lorry had been parked nearby. The lorry had been used to bring the tents and other equipment a few days or weeks before.

Between Sagman and Pertek.

The clouds began to break up and the sun shone in a sky that grew steadily more blue with every minute that passed. Although I had to walk all the way to the inhabited village the old men had mentioned, the scenery was so enchanting that I could not help smiling, my tiredness notwithstanding. I was now very high on the north-facing valley wall and could see for considerable distances in every direction except south where the reservoir was. However, in the other directions were hills, mountains, deep valleys, a meandering river, large flocks of sheep and goats, trees on the steep slopes and lots of beehives on a relatively flat shelf high above the river. The beehives suggested that the inhabited village was nearby. Moreover, ahead was a break in the ridge immediately to the south that would allow a road to turn right for Pertek. I had just about done it.

As I approached the gap in the ridge, I saw a woman aged about 35 sitting on a rock as she smoked a cigarette. She was not wearing a headscarf. She looked north toward the highest mountains of Dersim. With the ascent over I needed a break, so I said hello. When the woman replied in a friendly manner and patted the rock on which she sat, I knew she would not object if I rested beside her. We shook hands and I declined a cigarette, but I drank lots of the water in my bottle. The water had remained almost as cool as when I had taken it from the cesme at old Sagman.

It turned out that one of the old men at Sagman had rung someone in the village to look out for my arrival and the young woman with whom I was chatting had assumed the role of a welcoming committee. She was a jandarma enjoying a few day’s leave and had returned to her home village to spend time with family and friends. A female jandarma? This was most unusual in itself, but when she said she was an Alevi and unmarried (very few women in Turkey remained unmarried by the time they were 30), my surprise was compounded. However, she had a great sense of humour and was determined that I would meet her mother and a few other people in the village.

I was led to her mother’s house, an old place spread over a single storey, and encouraged to sit in the small garden in shade created by vegetation trained overhead. After the mother had been introduced to me and before she sat down to join in the conversation, she brought me some stuffed vine leaves, a stuffed pepper and two large glasses of fruit juice, all of which I gratefully consumed because I had had nothing since breakfast except water. The mother and daughter confessed to finding Sunni Muslims “a problem”, and the daughter confessed to enjoying alcohol when she was off-duty. I explained about the organic wine I had been given at Onar and the daughter laughed heartily, just as she had laughed earlier, when, after I had peeled off my anorak to reveal a damp shirt unfit for human wear, I tried to make myself look more presentable by combing my hair! Her laugh said it all: my effort was a total waste of time.

The village between Sagman and Pertek where I was fed.

My meal over, I explained that I had to get to Pertek before nightfall, something I was told would be no problem because it was only 3 kilometres away. The daughter took me for a short walk through the village where I met a few more people, then we kissed on the cheeks and I left for Pertek. The road soon provided excellent views over the town and the reservoir. Because I was descending all the time, less effort was required. Once on the edge of Pertek, I took a short cut across some derelict land on which had been built the occasional house or small apartment block. I emerged on the main road leading to Cemisgezek and Hozat, but the roundabout with the peace sign still lay about 2.5 kilometres away. So near yet so far from my destination. It was now that the fatigue really kicked in because there was nothing new to enjoy (although, walking toward the hotel a little later, there was another dramatic sunset).

Pertek.

Sunset, Keban Reservoir, Pertek.

I stopped at the same bufe as the night before to buy two beers and a packet of crisps, which was all my body craved because of the excellent food so recently consumed, then I took a few photos of the sunset. I lingered a while to chat with the hotel staff on reception because they looked bored, but was in my room by 7.45pm, just as the last light was draining from the sky. I stripped off, showered, put on the heavy towel dressing gown provided to guests for the duration of their stay and washed a few items of clothing. Next, I sat at the table in front of the window, opened the first of the two beers and began jotting down a summary of what had happened since waking that morning. Not all the day’s monuments had lived up to expectation, and many houses I had hoped to see no longer existed, but the scenery had been memorable from start to finish. I had walked 25 to 30 kilometres through some of Turkey’s most enchanting upland scenery and been driven through even more of it, and, as a consequence, felt confident I would return quite soon to delve a little deeper into what Dersim had to offer.

Sunset, Keban Reservoir, Pertek.

Sunset, Keban Reservoir, Pertek.