Due to the early start in Tunceli, I was in my room by 9.45am. However, I was out again by 10.15am with my bottle full of water taken from a tap in the spacious bathroom (I filled the bottle on many occasions during the day and was impressed that many places had the facilities for me to do so). What were my destinations for the day, provided everything went to plan? Hozat, from where I wanted to visit the ruined Armenian church in or near the village of Gecimli (in some sources, the church was misleadingly said to be in In, but In was about 3 kilometres from the church. Ergen was another name used to identify where the church was. Ergen was probably the old name for Gecimli), and Cemisgezek, a town with a a few important monuments of considerable age. Cemisgezek was also rumoured to have interesting old houses, but how many had survived to the present day I could not establish from afar.

Because getting to the ruined Armenian church from Hozat would probably involve a time-consuming walk along a road devoid of traffic, I hoped to access Hozat first, but I would allow the destination of the first lift to determine the day’s precise programme. I walked north from the hotel for about 1.5 kilometres to a roundabout where a right turn went to modern Pertek and a left turn went to Hozat and Cemisgezek. At the centre of the roundabout was the widely known sign of peace inside a circle first popularised by the anti-nuclear weapons’ movement, and on the sign was the word “peace” in many languages.

I had been at the roundabout for only five minutes when a minibus came down the gently inclined hill from modern Pertek. I flagged down the minibus and was told it was going to Hozat. Perfection.

At first, the road clung to the shore of the reservoir, but, once we had passed the turning for Sagman, a village I would visit the next day, it almost immediately began to ascend into the rounded hills from where there were extensive views over the reservoir and toward distant mountains. Almost every moment of the rest of the day was spent in glorious upland scenery, sometimes surrounded by mountains and sometimes with the vast reservoir in view. From the scenic point of view, this was to prove perhaps the most rewarding day of the trip. It is true that the scenery in Munzur Vadisi Milli Parki was more spectacular and enchanting, but what I encountered today was more extensive. Moreover, there were times when the scenery assumed an austere, even forbidding, character because trees were sometimes absent from view and rainfall in the region less frequent than further north and east. Suffice it to say that I was in remarkably beautiful upland scenery different in character from that in the milli parki. There were fields, orchards, pasture, wild flowers, large herds of cattle, very large flocks of sheep and goats, many small settlements worthy of examination (some small settlements lay along the roads, but most were some distance from and above them) and lots of very friendly and helpful people. Moreover, later in the day, as the sun began its descent toward the horizon in the west, the visibility assumed a clarity of exceptional quality. What more could anyone ask for?

The road to Hozat split from the one to Cemisgezek at a hamlet between Dorutay and Akdemir, and very soon entered a valley narrower than many in the area. The ascent to Hozat was gradual but consistent, and the mountains of the milli parki lay to the north. The closer we got to our destination, the more the scenery recalled that of the milli parki and the Ovacik area.

We arrived in Hozat, a small town on a gently inclined shelf above the valley along which the road had ascended. With mountains around it no one could fault its attractive surroundings, but Hozat was overwhelmingly modern and almost indistinguishable from a thousand Turkish towns of similar size.

By now I had been befriended by an Alevi couple with a remarkably liberal disposition who had travelled on the minibus since it left Pertek. The couple not only explained that Hozat was overwhelmingly Alevi, but helped me get to the ruined Armenian church. They had to visit some people in a village near the church. We retired to a tea house for glasses of tea and a cup of coffee each, and a three phone calls were made. A few people came for a short chat, then, about half an hour later, we climbed into a minibus driven by a man aged about 25. The Alevi couple stopped the minibus not long after it had set off to buy fruit, vegetables, cheese and bread, supplies for the people they wanted to see in what must have been a village devoid of shops.

We drove about 2 kilometres along the road toward Pertek, then took a left turn. The road crossed the river and meandered along the east wall of the valley. Most unusually, a sign beside the road junction indicated that Ergen Kilisesi lay 9 kilometres away. In 99 out of every 100 cases, minor Armenian ruins in Turkey were not signed for walkers or passing motorists. The only explanation I could give for this exception to the rule was that I was in Dersim where all minority communities had been brought together in a spirit of comradeship by decades of secular and Sunni Turkish oppression.

The road occasionally ascended to a considerable height and the views were outstanding. After driving about 7 kilometres, we took a left and ascended into a very small settlement on an exposed hillside. The minibus drew to a halt outside an old stone house with a flat roof with rooms arranged on only one storey. We had arrived at the house of the friends the Alevi couple wanted to see. Their male friend, a tall and hyperactive individual aged about 40, lived with his partner aged about 32. The couple were unmarried, which was most unusual in Turkey, even in urban centres such as Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir and Bursa which thought of themselves as being very liberal and progressive.

Although the couple in the house had recently installed some kitchen units and a new fridge and cooker, they lived a very simple life in the hills. But for a TV and a few electrical gadgets, they had little more than a family might have had that depended on agriculture to make a living (although there was an impressive collection of bottles with alcoholic drinks on a cupboard in the hall). Their main source of income seemed to be sheep and goats, many of which were temporarily confined to a rectangular enclosure of dry stone walls covered with a large blue sheet made of artificial material no doubt designed to protect the flock from the sun. But what confirmed I was in the company of a couple living an unconventional lifestyle by Turkish standards was a poster of Ibrahim Kaypakkaya hanging on the dark-coloured plaster wall of one of their rooms. I was in the company of communist sympathisers who had chosen to live their lives far from the madding crowd. This meant that they were far from the prying eyes of the police and other uniformed representatives of the Turkish state. Little things during the hour or so that followed suggested to me that both had strong sympathies for the PKK and that the male half of the couple may have fought on its behalf (the woman may have done so as well, for all I know). After she had prepared a wonderful lunch of mild white cheese, olives in a herb and oil dressing, tomatoes, cucumber, helva, bread, butter and tea (the tomatoes, cucumber and bread had just arrived from Hozat, but the cheese and butter were locally sourced. Both the latter were outstanding), the young woman pecked at her food, rolled her own cigarettes with tobacco grown in the Adiyaman area and discussed things as an equal with everyone else. However, not once did she smile. For the whole time she looked as if the problems of a blatantly unjust world, a world in which the oppression of the people least equipped to care for themselves was almost universal, were always at the forefront of her mind. Wearing shalwar, a grubby top and no headscarf or make-up, her slim frame and diminutive height were apparent to everyone present. Handsome rather than pretty, I nonetheless found it difficult to take my eyes off her. If her hands were not engaged in movement, she would prop first one foot and then the other onto the seat of her chair and exhale smoke by lifting her face to the ceiling, thereby allowing some of her long hair to fall from her shoulders down her back.

Suddenly it was time to go. I managed to take a few photos of the couple, although it was obvious that neither he nor she were at ease with me doing so (this confirmed that they were keen to be as inconspicuous as possible. They were radically opposed to religion in any shape or form, so the Sunni Muslim idea that it was wrong to photograph a female did not explain their concern about my desire to immortalise one half of the couple), but the farewells were warm and heartfelt (they had detected that my sympathies lay with the left, but I did not sympathise with communism, which so often replaced one tyrannical regime with another). The young man got ready to drive off in the minibus, so I and the Alevi couple who had befriended me on the journey from Pertek climbed aboard. We drove to the road leading to the Armenian church and, after about 3 kilometres, arrived in the village of Gecimli. The minibus was driven into the large garden attached to a house in the centre of the village and the man who had done the driving explained that the house belonged to his family. I met the man’s mother and father and was told that the church lay only 200 metres further along the road. After I had looked at the ruin, I was to return to the house from where I would be driven back to Hozat. As I walked toward the church through yet another village worthy of further examination, I had to fight back a few tears. Hospitality among the people of Dersim was of a quality I had never encountered before, not even elsewhere in Turkey, where, in my experience, hospitality exceeded that in any other nation state I had visited.

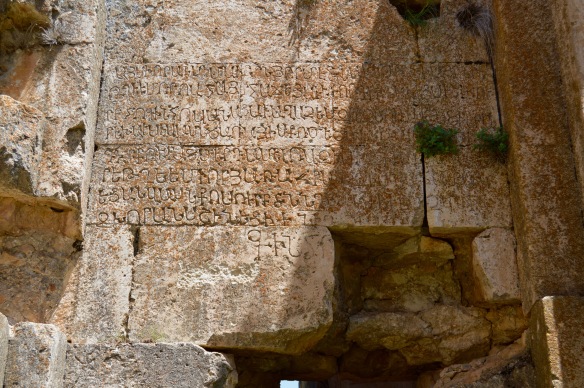

The ruined Armenian church at Gecimli was in very poor condition, but it must have been a remarkable building when complete. The carved stone decoration of the exterior conveyed something of its once-stunning appearance. Sinclair notes that the church had been part of a monastery. Today, only parts of the church remained.

Sinclair reveals that:

The church, which was dedicated to the Holy Virgin, and probably the whole monastery (that of Surp Karapet, or John the Baptist), was founded in 975/6. This was about 40 years after the Byzantine conquest of the Dersim and the Lower Euphrates valley. The monastery came into prominence in the early 15th century, when the Armenian and monastic church revival in Amid (Diyarbakir) and its district seems to have affected this area. It was probably in the 1420s that the church was overhauled: it was certainly refaced on the exterior, and the roof and vaults were probably rebuilt. The monastery was active during the whole of the 16th century. It is not clear when it was abandoned, but it was certainly empty by 1865 and the final abandonment may have taken place in the 18th century. Local tradition suggests some serious robbing of the stone in 1944, possibly in order to build a school – but this point needs clearing up by looking at the school.

The church was basilican in layout. Although almost the whole of the s. wall and most of the w. wall have been lost, and although nothing can now be seen of the piers which supported the arcades, the high, elaborately articulated w. façade and the longer n. façade retain their nobility and impact…

There is an apsed chamber, n. of the apse, at the e. end of the northerly aisle. The chamber’s entrance is rather darkened and partly hidden, as if at the end of a corridor, by a short wall extending westward from the end of the apse wall. The wall consists of a short blind arch and the pier from which the first arch is sprung.

The fine decorated portal in the n. wall is placed in the centre of the wall as a whole but e. of the middle point of the wall as seen from inside. The portal is brought forward on two buttresses either side of the doorway; to either side again are two buttresses. Otherwise the n. wall is plain. High in the faces of the two inner buttresses, above the level of the lintel, are panels consisting of a rectangle covered with interlace adjoining a rectangle of contiguous arches joined to one another by knots. Above the door is a heavily decorated lintel, now broken, and a semi-circular relieving arch. Plain engaged pillars run up either side of the doorway and flare outwards in the long, heavily overhanging leaves of the capitals beneath the lintel. Along the outer border of the relieving arch, across the top edge of the lintel’s face and down the lintel’s two ends runs an undulating branch with leaves of an odd, simplified, less supple form than are found in standard Selcuk decoration… At either end (of the lintel) we can see a panel decorated with a plant whose stem divides, is reunited and curves to fill the whole rectangle with its tendrils. At the l.-h. end of the lintel much of the next panel can be seen; the remainder is damaged…

E. façade. Here the triangle of masonry between the apse and the two side-chambers is partly carved out in two wide V-shaped niches. The apse was lighted by a double window whose sills were at head height: however, the windows’ frames have been lost, apart from the outer vertical member of the r.-h. window. Here we can see a line of rosettes and other designs inside circles joined by knots… The composition centring on the window in the apse of the northerly chamber is reasonably complete. The window is flanked by tall panels. Engaged pillars rise between the panels and the window, and provide the support for the arches covering each of the three. Each pillar rises out of a sculptured element resembling a stepped base, which is probably modelled on a stele base. These bases bear very shallow decoration. One of the bases for the two engaged pillars which rose between the apse’s windows is left. Here five arches are deeply carved in the face of the base.

I have quoted extensively from Sinclair because, although not everything he saw in the 1980s has survived, the church is still such a notable monument that people should know what has already been lost, and what could be lost in the future if the ruin is neglected for much longer.

I returned to the house where the minibus had been parked and, after brief chats with everyone present, said goodbye with particular regret to the couple who had befriended me on the minibus from Pertek to Hozat. The young man ushered me into the front of the minibus, picked up a friend who wanted a lift to Hozat, and, after exchanging the V-sign with a few males gathered around an electricity pylon, we left for the main Hozat to Pertek road. The scenery along the dirt and gravel road all the way to the junction looked even more enchanting (especially because we were looking north toward the mountains around Ovacik), not least because I had attained the day’s first goal and it was only just after 1.00pm. I decided to risk a visit to Cemisgezek, although I would probably have to rely on hitched lifts both ways.

We arrived at the main road and I thanked the driver for everything he had done on my behalf. I offered to pay for at least some of the petrol he had used, but the money was waved away with an expression of mock anger. Not for the first time during the trip, a tear or two began to form.

I began walking south and was soon ascending to a rounded summit with pasture and wild flowers from where I could see many kilometres in all directions. With the views changing very slowly, I could appreciate the landscape even more than in a car or a minibus, not least because nothing created an obstruction between me and my surroundings. I was in a stunningly beautiful part of eastern Turkey and thought longingly about how magical the road between Hozat and Ovacik must be. Another year, with luck.

After walking about 3 kilometres, two off-duty jandarma kindly gave me a lift to where the road from Hozat joined the one from Pertek to Cemisgezek. Before arriving at the junction, we stopped at a roadside cesme to fill our bottles with chilled water from a pure source in the nearby hills.