But things changed very quickly and the changes were for the worse, as the article below in “The Guardian” newspaper (25.7.15), confirms. Turkey at last decided to take action against the Islamic State (good), but, for reasons difficult to understand, it at the same time attacked PKK positions in northern Iraq (bad), even though the PKK had done nothing substantive to threaten the ceasefire between the Turkish government and the PKK:

Turkey launched overnight air strikes against several positions of the outlawed Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK) in northern Iraq for the first time in four years, the country’s government has said.

The air raids put an end to a two-year ceasefire between the Turkish government and the PKK, severely endangering the already fragile peace process started in 2012 in an attempt to end a bloody conflict that has killed more than 40,000 people over 30 years.

According to the office of the acting prime minister, Ahmet Davutoglu, the bombs hit several PKK targets in northern Iraq including shelters, bunkers, storage facilities and the Qandil Mountains, where the PKK’s high command is based. Turkish fighter jets also targeted Islamic State positions in Syria for the second night in a row, the statement said. In addition to the air raids, the Turkish military carried out artillery attacks against the Islamic State in Syria and the PKK in northern Iraq.

“Strikes were carried out on targets of the Daesh (Islamic State) terrorist group in Syria and the PKK terrorist group in northern Iraq,” the prime minister’s office said, adding that all anti-terrorism operations were “carried out indiscriminately against all terrorist groups”.

In a major tactical shift this week, Turkey decided to take a more active role in the US-led coalition fighting against the Islamic State, agreeing to open its air bases to allied forces as well as carrying out its own air raids. It is the first time Turkish fighter jets have entered Syrian airspace to attack Islamic State militants on Syrian soil. Previous air raids were conducted from the Turkish side of the border, according to the Turkish government.

Speaking at a press conference on Saturday, Davutoglu said almost 600 terrorism suspects had been detained in co-ordinated raids on Friday and Saturday, including people with alleged links to the Islamic State and the PKK. “I say it one more time: when it comes to public order, Turkey is a democratic state of law and everyone who breaks that law will be punished,” he said.

In a first reaction to the attacks on their camps, the PKK leadership said that the ceasefire with Ankara had lost all meaning. “The ceasefire has been unilaterally ended by the Turkish state and the Turkish military,” said a statement on the PKK website on Saturday. “The truce has no meaning any more after these intense air strikes by the occupant Turkish army.” The group said the fallout and consequences of the overnight attacks would be disclosed later.

Mesut Yegen, a historian on the Kurdish issue, said that it was too early to say that the peace process was over. “So far, the PKK has not given the order to fighters on the ground to launch a counterattack, but it is clear that the peace process has been weakened substantially,” he said.

It was unlikely that either the Turkish military or the PKK wanted an all-out confrontation. “As long as the attacks remain limited to the air strikes, there is hope that the peace process will continue,” Yegen said.

The raids on both the PKK and the Islamic State came after a wave of violence swept across the country last week. On Monday, a suicide bomber killed 31 Kurdish and Turkish activists in the southern border town of Suruc in an attack that Turkish officials blamed on the Islamic State.

After the bombing, tension has risen to dangerous levels in the predominantly Kurdish south-east, where many have long accused the Turkish government of directly supporting the Islamic State against the Kurdish struggle in Syria, a charge Ankara vehemently denies.

Later in the week, the People’s Defence Force (HPG) – the armed wing of the PKK – claimed responsibility for the killing of two police officers in Ceylanpinar, a town on the Syrian border, in retaliation for the Suruc bomb. A policeman was killed in Diyarbakır on Thursday, while another officer was kidnapped there on Friday night. Violent protests against the ruling AKP’s failed Syria policies and their stalling of the Kurdish peace process have erupted in several cities across Turkey.

In two subsequent anti-terror raids across Turkey, hundreds were detained on Friday and Saturday, including people with suspected links to the Islamic State and to the outlawed PKK.

Ahmet Yildiz, a farmer and shepherd in Semdinli, a small town nestling between the Iranian and the Iraqi borders, said the sound of fighter jets kept his family up most of Friday night. Late on Friday, PKK fighters attacked a local police station wounding three officers.

“The planes are all around in the mountains,” Yildiz said. “I bought a flock of sheep because I believed that peace was finally going to come. But now I don’t know what will happen. I don’t know if I can take the sheep up to the pastures. I am very sad; we all are.”

The leftist People’s Democratic Party (HDP) said it was time to stabilise the peace process. “We underline again how very much Turkey needs peace and a solution [to the Kurdish issue]. It is possible to solve our societal, historical and political problems through mutual dialogue, negotiations and through the development of democracy,” a statement said on Saturday. “The increase and perpetuation of violence will not bring a lasting, democratic and egalitarian solution for any side, or any part of society.”

The update below summarises matters at the end of August 2015. It suggests to me that Turkey is entering a period of uncertainty that will be detrimental to most of its citizens:

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has approved the make-up of the provisional government that will run the country until the 1st November elections, including for the first time pro-Kurdish MPs.

Prime minister Ahmet Davutoglu was tasked with forming a caretaker government earlier this week after he failed to form a coalition government following an inconclusive vote on 7th June.

The two pro-Kurdish legislators are from the People’s Democratic Party (HDP), which for the first time managed to pass a 10% minimum vote threshold required for it to be represented in parliament in the June election. Davutoglu said HDP legislators Muslum Dogan and Ali Haydar Konca will become ministers in charge of development and of relations with the European Union.

The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost its overall majority in parliament for the first time in 13 years in the June polls. Erdogan appointed Davutoglu to form an interim “election government”, which, according to the constitution, must be made up of all parties represented in parliament.

The cabinet spots are divided up according to the parties’ share of seats in parliament with 11 going to the AKP, five to the second-placed Republican People’s Party (CHP) and three a piece to the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the pro-Kurdish HDP. Opposition parties have refused to take part in the interim government, making the HDP – which the government accuses of being a political front for the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) – and the AKP major partners in the new cabinet.

Speaking to his party’s provincial heads earlier on Friday, Davutoglu said: “We will work just like a four-year government as we are heading toward 1st November.”

In a deviation from the party line, MHP legislator Tugrul Turkes, son of the MHP’s founder, Alparslan Turkes, accepted an invitation to serve as a deputy prime minister in a move denounced by the party’s leadership.

Davutoglu had to appoint non-partisan figures to fill the seats snubbed by the opposition parties. Selami Altinok, former Istanbul police chief, was appointed interior minister and foreign ministry undersecretary Feridun Sinirlioglu was named as the new foreign minister.

The 1st November general election was a success for Erdogan and the AKP. It has been judged by European Union observers to be free but not fair because it took place in an atmosphere of fear and intimidation against a backdrop of escalating violence and the detention of government opponents, members of the media included.

The AKP won an overall majority of 317 seats with 49.5% of the vote (in fact, the AKP secured about four million more votes in November than in June). The AKP won the election on a pledge to bring stability and security out of chaos, but a majority of voters conveniently ignored that Erdogan and the AKP were the cause of the chaos in that they broke the ceasefire with the PKK and directed more military force against the Kurds in Iraq and Syria than against the Islamic State.

In my estimation, the election result is a disaster for Turkey. Why? Because it will unleash dangerously high levels of Turkish nationalism and give to the Islamists, whether moderate or otherwise, the power to push through reforms that make the state far more sympathetic to mainstream Sunni Islam than is already the case. All non-Turks and non-Sunni Muslims have reason to regret that the AKP’s decision not to negotiate seriously to create a coalition government following the June election has paid off, for the AKP at least, if not for anyone else.

One of the few positive outcomes of the election was that the HDP won more than 10% of the vote (10.7%) and is therefore still represented in parliament, but its share of the vote declined from June and now it has only 59 MPs. Perhaps inevitably, unrest in Diyarbakir followed. In Silvan, where some of the local Kurds had declared independence from the Turkish Republic, the result was greeted with considerable worry. In fact, across all of Turkish Kurdistan and in Tunceli province, majorities were deeply troubled that the AKP once again ruled alone. By the time we get to the next general election (unless one is called earlier than required), Turkey will have been ruled by one party, the AKP, for no less than 17 years, despite the few months this year (late August to the end of October) when the provisional government was in power, a government that included non-AKP MPs (see above).

Another positive outcome was that the AKP did not secure the 330 MPs required to call a referendum to amend the country’s constitution.

Just for the record, the CHP got 25.3% of the vote and 134 MPs and the MHP got 11.9% of the vote and 40 MPs. A small number of people voted for parties that did not reach the 10% threshold required for representation in parliament. The percentage of women MPs declined from 18% to 14.7%.

The “Today’s Zaman” website has an excellent chart revealing how many people voted for each party in every province.

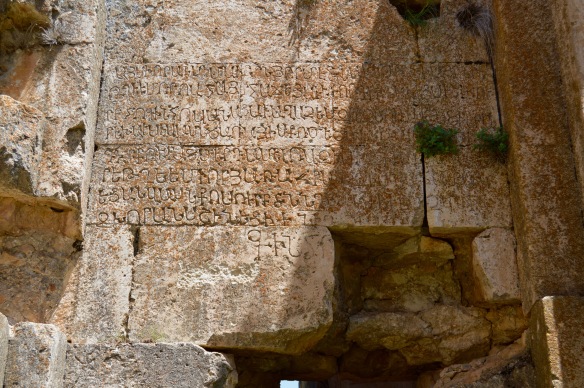

P.S. I recently read that Turkey would like the deserted medieval Armenian city of Ani, which overlooks the border with the Republic of Armenia east of the city of Kars, declared a world heritage site. Neglect and much worse mean that very little of this once-magnificent city remains, but here is further evidence that at least some Turkish citizens in positions of political authority recognise the importance of a few Armenian monuments, albeit primarily in the hope that, by preserving what remains, tourist revenues in a remote region will increase.